Library of Congress Bicentennial Celebration Presentation - Page 23

San Diego. Completion required five years of weekend travels by authors Hanson

and Miller, and photographer Mortensen. Along with the Janson Bridge, it will

probably be the most enduring legacy of the P.F.D.A.

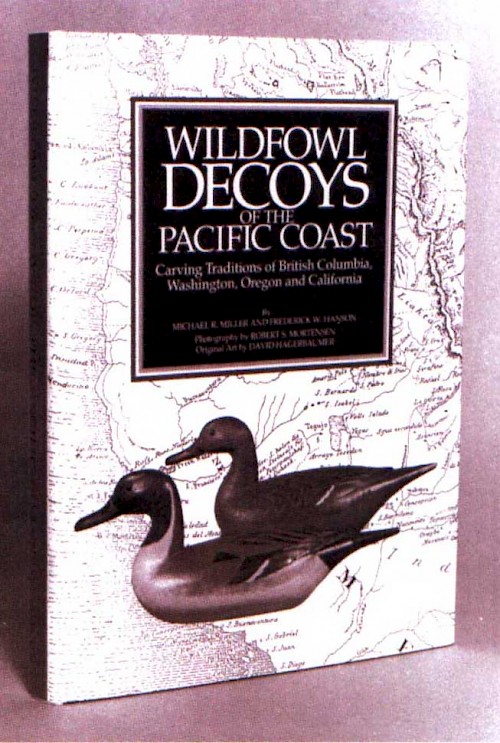

In 1990, the book that had been eagerly anticipated by collectors for over five years, Wildfowl Decoys of the Pacific Coast, co-authored by Dr. Fred Hanson, and U.S. Fish and Game Biologist Mike Miller, had at last been published. The big book had exceeded expectations. Because the authors had labored five years, covering a vast territory, they chose to spare no expense in turning out a handsome product. Illustrated with hundreds of photos, the book upheld western decoys as exemplary folk art. The text not only included short biographies of the carvers, but also eye witness accounts by survivors whose formative years included the Great Depression, and the upheaval of World War 11. Here was a comprehensive work that would never be equaled (those eye witnesses might not see another millennium), and an enduring legacy in which every collector who had opened his doors to the researchers, loaned his notes, photos, documents, or contributed his knowledge, could claim a modest share.

With such an imposing book in hand, decoys as folk art, artform, or "Californiana" were concepts easily sold to those grey guardians of culture, the museums. Soon after the book came out, the San Francisco Craft & Folk Art Museum had a copy to help them visualize a two month exhibit titled "The California Duck." In 1994, the Sacramento City History Museum devoted two months to the "Historical Significance of Decoys in California," a showing of both antique and contemporary decoys, with art-in-action carvers on hand to explain the significance of both. Two years later, the Cowlitz County Museum, in Kelso, Washington, recalled a local legacy with "Art on the Water: Decoys Along the Pacific Flyway." Here at last, near the historic waterfowling area at the mouth of the Columbia, someone had gotten it right. This was the largest exhibit yet assembled, with over 280 decoys, plus mounted birds and hunting artifacts from two major collections. Public enthusiasm was high, critics expressed admiration, other collectors were moved to offer choice additions, and a pleased museum staff, calling this show a "breakthrough," held the show over for several months.

This dramatic rise in the status of abandoned old decoys can best be illustrated with a final anecdote. In 1974, the widow of a wealthy San Francisco decoy collector invited Jim Keegan, Don Yost, and this writer, to come and assess the value of her late husband's large and eclectic assortment. They were not all prizes, but the core of the collection was solid, and he had at least three pairs of coveted "Fresh Air Dicks" (worth about $10,000 dollars on today's market), with many more decoys in the basement that were negotiable. Sometime later, after the inventory had been made, the lady informed us that she had offered the collection to the Oakland Museum, but had been turned down because neither by word or letter could she make Staff understand what she was trying to deliver, and Staff hadn't the foggiest notion what they might do with the things once they got them.