Library of Congress Bicentennial Celebration Presentation - Page 4

making much to the decoys as early as 1923, but somehow Bellport gentry neglected to send

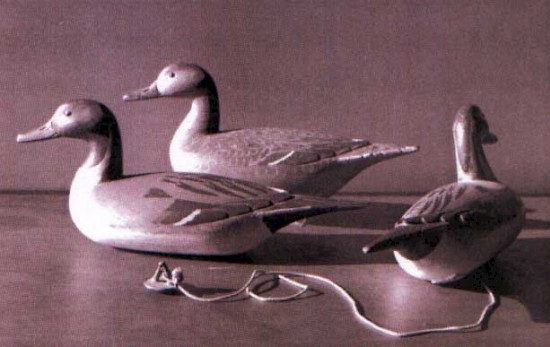

him an invitation. His huge lifetime production of perfectly matched handmade rigs is a legacy

to carvers and a joy to collectors.

The New England decoy makers, officials and judges at Bellport, were all business. They could remember the era of unrestrained market hunting for meat and plumage; they were accustomed to handling rigs of decoys, and weren't playing at make-believe. Any suggestion that this might be a craft or art show, and that what they were handling would turn out to be "folk art" or "floating sculpture," would have been met with incomprehension or derision. Nevertheless, an eyewitness, writing his recollections 41 years later, drops a hint that some artistic temperament had been observed. Today we call it "bitching about the show results" and it remains the single most honored tradition left over from Bellport. Here is yet another reason why "Art isn't for Sissies." has emerged as a guiding principle of the Pacific Flyway Decoy Association.

At the conclusion of Bellport '23, the promoters, having accomplished their aims, concluded that this unusual show might play well uptown and in 1924, they organized another contest in New York City, at the Winchester Sportsmen's Headquarters on 5th Avenue. Only four dozen entries were received, and after one more effort at the Abercrombie & Fitch store in 1931, no more attempts were made for a decade.

Among the attractions at Bellport had been some displays of old decoys, and of these the most outstanding were from the collection of New York architect, Joel Barber, another resident of Long Island. Mr. Barber had the artist's eye and education to advance the elitist concept of old decoys as folk art, "Americana," and "floating sculpture". In 1934, he put these observations onto a slender book, Wild Fowl Decoys, artfully illustrated with drawings and photos, and had an elite edition leather bound for the carriage trade. He had been aided by duck hunter, editor, author, and publisher, Eugene V. Connett. The book made all the right connections, and larger printings followed. Soon Barber's sentiments on the art-of-the-decoy would inspire generations of collectors from coast to coast. In 1954, a paperback edition was printed by Dover Publications and remains a collectors item in whatever condition it can be found.

In 1941, decoy contests were once more revived as an addition to the annual National Sportsmen's Show in New York City, but after one successful show, the war intervened. In 1947, with hunters once more afield, the planned "Nationals" were resumed in New York City. Joel Barber, whose book certainly sustained this nostalgia for revivals, served as a judge along with Ralf Coykendall, artist Lynn Bogue Hunt, Dr. Edgar Burk (a household name by virtue of his decoy illustrations in books by Eugene V. Connett), and a formidable collector from Belford, New Jersey, Mr. William J. Mackey, Jr. Some of the contestants who entered the New York Nationals would soon bear household names as well: "Shang" Wheeler, L. T. Ward &Brother, Ken Anger, Bill Schultz, Eugene V. Connett, and Ted Mulliken of Wildfowler Decoys Company. But the Nationals ended in 1951. The numbers had never been large and the era of cheap and expendable plastics had changed decoys forever. Hunters were content with plastic, so who would predict a future for these heavy, fragile, labor-intensive floating sculptures?

Without a future, wooden decoys would eventually pass from the hands of hunters who now abandoned them, into the hands of collectors who now appreciated them. But a wartime generation of young men were coming into the field who took note of this passing and thought they might be missing out on a part of their heritage, and in 1960, another series of Nationals was instituted at the annual Northeastern Sports Show in upstate Syracuse, New York. Decoy collecting was active in the Midwest, and in 1963, a young collector in Burlington, Iowa, Mr. Hal Sorenson, began publishing a quarterly, Decoy Collector's Guide -much to the annoyance of Mr. Bill Mackey, already at work on his enduring masterpiece, American Bird Decoys, which, published in 1965, would establish him as a celebrity, an incomparable authority, and the first among household names from coast to coast.

With his success came opportunities to arrange special exhibits from his enormous collection, and Mackey, a salesman and gifted raconteur whose blunt personality was singularly adapted to the podium, accompanied select showings of his birds in the IBM Gallery in New York City, the St. Paul Art Center in Minnesota, and the Paine Art Center in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. These unusual exhibits inspired emulation, and soon the Chicago Art Institute arranged a display of recently acquired decoys from the Midwest and the Illinois River; a gift of Midwestern collector, Ralph Loeff. The U.S. Pavilion at the Toronto Exposition of 1967, offered a comprehensive exhibit of regional decoys arranged by collector / author Adele Earnest (The Art of the Decoy - 1965), and the Milwaukee Public Museum began expanding its decoy acquisitions under the guidance of curator / carver Bill Schultz. In ,1970 the Mackey traveling collection was exported by the U.S. State Department as part of its exhibit at the World's Fair, in Osaka, Japan. Thus, in a span of twenty years, old handmade wooden decoys had risen from service as doorstops and firewood to the status of corporate art, institutionalized art, and government-sanctioned floating sculpture of international significance.

In 1968, Bill Mackey was invited west to give a lecture at a Ducks Unlimited gathering in San Diego, California.On this occasion he met a personable young collector, Don Yost, of Berkeley. Within a year Mackey came West on a similar errand in the Pacific Northwest, and at the request of Don Yost, stopped for an overnight visit, to look over a representative collection of west coast decoys and to meet some collectors of the Bay Area.

Looking back, it ought not to have surprised us that Bill Mackey was so unimpressed with western decoys that the could barely be made to look at them. Like the sales manager that he was, he had the knack of looking after his reputation and his interests, and he had a grasp of the limits of his turf. In addition, he had imposing bulk, unassailable credentials, and a limitless supply of anecdotes - a combination that could hold a table of collectors spellbound for an evening. It was under this spell that western collectors were finally moved to elevate their ambitions, and that is how young Don Yost was inspired to organize the first west coast decoy contest in the John Berry Boatyard in Berkeley's Aquatic Park, in 1971.